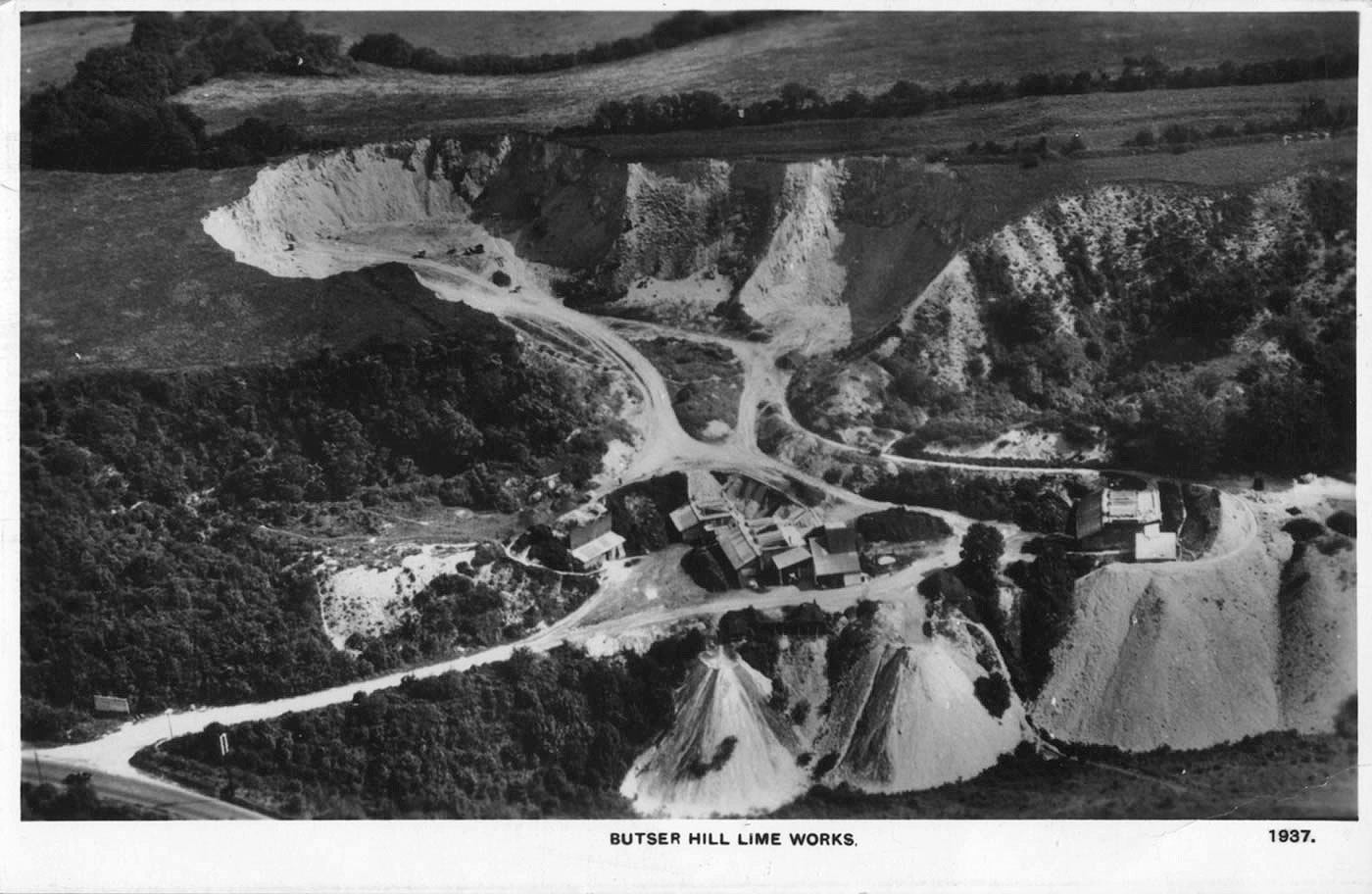

We, my wife, daughter Ann and son-in-law Douglas, were having our usual after meal reminiscence one day when the subject of lime burning came up. Ann and Douglas mentioned how the chalk pits at Amberley had become overgrown and derelict and how the site there now belongs to a museum. Whilst talking, a little idea developed in my mind and I said that I had never seen any documents about our local limeworks at Butser Hill. My idea was to record my memories of lime burning there. Another reason for wanting to describe this process is that my father was a lime burner by trade, also becoming sole charge of the works known as Butser Hill Lime Works.

Before I begin to unfold my memories, I ought to clarify who I am and where we lived. I myself am George Chitty (better known as ‘Sonner’ in those days) the eldest son of Mr and Mrs George Chitty. My mother and father first lived in one of a pair of cottages along the Petersfield Road just outside of Buriton where I was born. From there we moved to Butser Hill, Lime Kiln Cottage. The Sewards of Weston ,who owned the lime works, had the cottage built for my father, as you might say ‘to be on the job’. The cottage was situated on a rise a short distance from, and overlooking, the works. It also had a beautiful view of the hangers of Froxfield. For me it was phenomenal; that could be another story! I was five years old when we moved to Butser (about 1920/21) and so I grew up with lime burning although I was never introduced to the trade.

I will endeavour to give a summary of the lime burning activities.

The day started with the men arriving at 7.00am. I must mention that these workers had a distance of two or three miles to travel, some even further, with only push bikes or even “Shank’s pony” for one or two. I well remember Alf Butt who would walk from the other side of Petersfield and arrive at 6.30am to start at 7.00am. Then, after a day’s hard graft, he would have to walk back home; no travelling time in those days. Of course, I’m going back to the 1920s and early 30s. In those years the men had to work and work hard to uphold a job and in all weathers. The number of men employed at the kilns was between 15 and 20.

First of all I’ll describe the workings at the chalk pits. There were two kinds of chalk, referred to as white and grey. Grey was mainly used for the building trade such as mortar and plaster, also for agricultural purposes. The white was more for plaster mouldings and whitewashes. The grey came from the lower pit and the white from the higher regions. The chalk face was about 50-80ft. This is where the workman had to keep a vigilant ear and eye open at all times; a small trickle of chalk falling was a sure sign of an avalanche. If this did not happen, then dynamite would have to be used. Both produced some quite large boulders. These then would be taken apart with iron wedges, tongs and sledge-hammers, then with pickaxes to the required size, not forgetting the brute force of manpower. The explosives were stored in a small concealed dug-out with a thick brick wall and a very solid iron door. My father kept the keys at home.

The hewing of chalk was particularly crucial : if it was too small it would burn too hard and if it was too large it would leave a core of unburned chalk. Six to nine inches roughly would be the size. The most important were the pieces that formed the archway to the fire chamber which was about 24 inches in length. By the way, warning when blasting was by word of mouth relayed along the way: “Take Cover”. You really did have to run. I remember sheltering under the lean-to of the kilns about 300 yards away when a shower of chalk came over. I expect Dick put a little extra powder in that day.

After the chalk was, shall we say, dressed it had to be conveyed to the kilns. This was by means of a light rail track and metal trolleys. Dick Bridle was the man to carry out this task. The trolley piled high with chalk would be given a little push by a couple of other work mates to start it rolling, then Dick would take over, hopping up onto the lower rail. From here on the journey from the pit to the kilns was all down hill. This is where Dick had to use all his wit, skill and strength to slow the thing down. With a full load, a gathering speed of 30-40 mph could be obtained. The braking system was really a Heath-Robertson affair. The brake was a small bough of a tree (oak or ash) whittled to shape. The action was to place the timber under the middle bar of the trolley and over the top of the wheel, then press down with all your might. There were only a few occasions when Dick had to jump for safety. Perhaps when the brake handle broke or the vehicle came off the rails. When down and unloaded, he then had to push it all the way back : 10-15 times a day.

The trolleys were a playground to us boys, of course – but only when the coast was clear. They usually ended either coming off the rails or being overturned. Although Dick knew that we were the culprits he never did complain to my Dad.

Now we come to the kiln side of the works. There were two kinds of kiln. The first two were known as the draw kilns, the others were just kilns of which there nine in a two, a three and a four. Firstly, I will endeavour to portray the draw kilns. There were a pair of these built into a fairly high bank so as to give two working areas – one up and one down, top for filling and bottom for drawing out. The size of the kiln was about six to eight feet in diameter and roughly fifteen feet in depth, built in brick. Naturally, the fire chamber would be special fire bricks. At the base was a draught passage, then above were the firebars where the fire was laid. The aperture size of the fire hole was about three square feet. Above the fire was another set of bars, their purpose was to retain the lime from falling through. The whole of this bottom area was covered in with a lean-to shed.

We now go to the top by the way of a zig-zag climb. Working at the top was just a matter of filling with chalk and coke: layer of chalk, then layer of coke. Once the fire was lit and the coke started to burn, there was no need for the bottom fire. It would keep slowly burning day after day providing what was taken out was replaced.

Now comes the extraction of the lime but I’m a little vague about this operation. My Uncle Albert was the man in charge of the draw kilns. I know he would pull or twist the retaining bars to let a few pieces of chalk to fall through onto the lower bars. He would then take out each piece and examine it to see if it was all lime or half chalk. The difference being that if lime, it would be light in weight and would have a china-like ‘ting’ to it. Any piece that was not quite burnt through, was not altogether wasted. With his little hammer he would tap all around. The lime would fall off and leave an egg shaped core of chalk. There he had two wheel barrows, one for chalk the other for lime. The lime was stored and the chalk wheeled to the tip. Just envisage each piece of chalk that came out of the pits man-handled three or four times. When enough lime was stored, the majority would be ground to a fine power for agricultural purposes.