School Games

Percy Legg explained that children were never taught any sports at school in his days. Games like cricket and football “we would have to learn the hard way on Saturday afternoons with the bigger boys in the village, on the village green”.

But it would seem as though playground games changed very little over the decades. Miss Amy Bone, who was at the school throughout the 1890s, recalled that “we used to have set seasons for certain games. Whip-a-top, hoop and skipping were all carefully defined”. In a letter to the Petersfield Post in 1992, Esme Bridger remembered “skipping in the playground and spinning out tops” when she was at Buriton school in the late 1920s. And Percy Legg recalled playing playground games, such as conkers and marbles – “both under the wall in the schoolyard and under the old Rectory wall where the yew tree provided shelter”.

Hops, Shoots and Epidemics

In the days before the First World War, school would often be interrupted for hop-picking and for ‘beating’ for local shoots. The school log books record that many children were often absent during May because of hop-tying and then again later in the year when it was time to pick the hops. In May 1891 the headmaster wrote: “Owing to hop tying attendance is very bad indeed. I have visited the school managers and parents and also sent lists of irregularities to the Board Meeting but, with the exception of kind help from the Rector, I am not backed up in any way; in fact, some of the managers insist on the children being in their fields tying hops during school hours. Our efforts really seem useless. There are a few families here who defy the school in every way and ought to be made an example of – but nothing is done.”

School used to break up in mid August for a six week ‘Harvest Holiday’ but this was often adjusted if the hops or corn were early or late.

In winter months shooting parties also interfered with the attendance of boys. Notes like the following are not uncommon in the headmaster’s log books – this one from October 1890: “Attendance poor in consequence of some of the lads being employed for beating purposes. We struggle all we can to get regularity but 8d for a day’s pay and a rabbit is a great temptation and the school suffers.”

Washing days also regularly kept some children at home but illnesses took a far more serious toll on school attendances with the school being closed on a number of occasions to try to help stop the spread of epidemics: “School closed through illness (bronchitis and influenza) since last Monday. There is scarcely a house in this village and at Weston in which there is not illness. Several of the parents and young children have died” (January 1892).

Apart from influenza and colds, other outbreaks of illness recorded in the school log books include diphtheria, mumps, scarlet fever, chicken pox, measles, smallpox, whooping cough, ringworm and “eruptions of the skin”. Many outbreaks resulted in deaths of young children.

Cold classrooms probably contributed to the levels of absence due to sickness. In December 1925 the headmaster wrote “I have today asked if something cannot be done to warm my classroom during the winter months. At 9am the temperature of the room is rarely more than 37 degrees and it never rises above 45 degrees at any time during the day in cold weather. A small fireplace and a small anthracite stove are inadequate.” It was 1963 before electric radiators could be installed in the classrooms and used in place of stoves. With children walking to school from all over the parish, they would often arrive wet on rainy mornings and would have had to stay wet all day as there was nowhere to dry their clothes.

Lessons could also be interrupted simply by a lack of daylight as it was not until 1935 that electric lights were available. The school log books indicate a number of occasions when it was “so dark that after 3 o’clock one could hardly discern one child from another”. Normal lessons had to stop and the children would sing songs. There were also special closures of the school during the Second World War for ‘the potato planting holiday’.

The War Years

Mary Kelsey can remember schooldays during the Second World War. “It was a sad time but there was also some excitement for the village children as we would go to school at nine and at about ten o’clock we would look to the door to see if we had any new playmates. After a bad night of air-raids in Portsmouth, families would turn up in Buriton to see if their children could join the school. School was very squashed and crowded. We tried to keep some splits of age and abilities but often Miss Pleasant had to handle everybody as one big class. Some relief teachers came and the church hall was used as a spare classroom. It had a terrible old black coal stove which used to smoke and so children had to go outside from time to time.”

“If children heard an air-raid warning, they were all supposed to rush into the school and carry out their safety procedures. Inevitably, most of us had a good look round first to see what we could see before we rushed to school ! The safety procedures, which the children practised every morning, involved everyone diving under their desks (which were arranged in groups of four) grabbing their own chair and pulling it in towards the desk so that the back lent onto the top of the desk and the four legs stuck outwards. Although this procedure was practised every day, it never had to be used ‘for real’. On the one occasion that a plane flew overhead, most of us stayed outside for a good look before going indoors and gathering under our desks !”

Records from the war-time note how it was decided that senior children from the village going to Petersfield Senior School should receive their education in Buriton for the duration of the war. In spring 1941, however, conditions at the school became tense. In addition to the senior children, there were large influxes of evacuee children who were housed in hop-picking huts. By May there were 194 children on the school books (and instructions to take 30 more) but only 132 seats. Arrangements were then made to use the church hall and to obtain extra furniture. As well as the over-crowding, the “condition and habits” of some of the refugee children living in the huts led to some complaints from local parents and requests for them to be seggregated from local children. This was resisted and the school nurse was asked to “deal with any of the children not found to be in a proper state of cleanliness”. In 1944 it was agreed to reorganise Buriton school as a junior school with children over eleven going to Petersfield.

More recent changes

The main changes to the outside appearance of the school since the second world war are the addition of the kitchen and of the wire fencing around the edge of the playground. In the road, the stream which used to run from the top of the High Street down to the school before disappearing under the pavement, has gone. The stream itself was considered to be ‘out of bounds’ but the children used to have great fun in this area both in and out of school hours. Mary Kelsey recalls that the stretch along the school meadow was known as ‘the banks’. “There weren’t many big trees then, it was lots of little bushes and saplings. There were lots of little paths in this area where children played. If anyone did fall in to the stream on a school day (not an uncommon occurrence!), the only way to avoid a telling-off from Miss Pleasant was to take your shoes and socks off and put your plimsolls on and swear that you hadn’t brought your shoes that day. She probably knew what was going on !” The stream used to start just above the cross roads (where the signpost is now). There were little white railings there upon which children practised their ‘circus tricks’ – with the most daring ones trying to walk underneath Kiln Lane, coming out near to where the bus stop now is.

Tony Carter, who was also at school in the years immediately after the Second World War, particularly remembers the introduction of school radio. He explains that “the children had been told about a week in advance that the school would be getting a radio. When the man appeared with it there was a great debate about where it should go. Eventually it was decided to put it up on a windowsill, out of reach of all the little hands. In fact, only Miss Pleasant could reach it – even Miss Coles, the other teacher, had to stand on a chair to reach it !”. A television was not installed until September 1969.

Time off for hop-picking was still common and, once you were a certain age, children would get a special little green permit to show to Miss Pleasant who would then give permission for them to go and do three weeks picking rather than attending school.

For one evening a week the school became a village library with two of the best behaved children being allowed to stay behind after school to help Miss Pleasant act as the librarian. The library service used to bring big wooden crates of books out to the school.

As with the rest of the village, mains drainage and modern sanitation are relatively recent innovations. The school log books record that water-borne sanitation was installed early in 1958. Earlier, in 1924, the log books had described in some detail how a new system of “five buckets in the girls lavatories” had commenced: “three, reserved for urinary purposes, contain a supply of peat, moss and turf whilst the remaining two, marked ‘D’ (dry) contain a supply of sifted dry earth. Paper (cut) is supplied for use in the girls ‘D’ lavatories and in the boys lavatories. Monitors (one senior boy and girl) report every morning after playtime.”

Teachers and Staff

In the spring of 1887, records show that the headmistress of Buriton National School was a Miss Baldwin, with a Miss Welstead as an assistant. But both were given notice by the school managers in July 1887 “that their service will not be required after Xmas next and that if they should prefer to leave at Michaelmas the Managers will not object”. It was also “Resolved that a Master be obtained to enter on his duties when Miss Baldwin leaves, with his wife or sister to act as an assistant” at a joint salary of £60 to £70, together with “house, coals and firewood” and “half the nett Government Grant”. It appears from the minutes of the meeting that the managers were keen to enable village boys to attend the school (“instead of them being obliged as at present to go into Petersfield”) and that they felt that “the present Mistress was unable to undertake the charge of boys”. Another assistant mistress, Miss Titmouse, was retained as Teacher of the infants at a salary of £35 without house rent or extras.

The minutes of the Managers’ Meeting of November 1887 show that the school’s first Master, Henry A Allison, was appointed along with Mrs Annie E Allison as Assistant. The school log books indicate that Miss Titmouse continued as an assistant mistress.

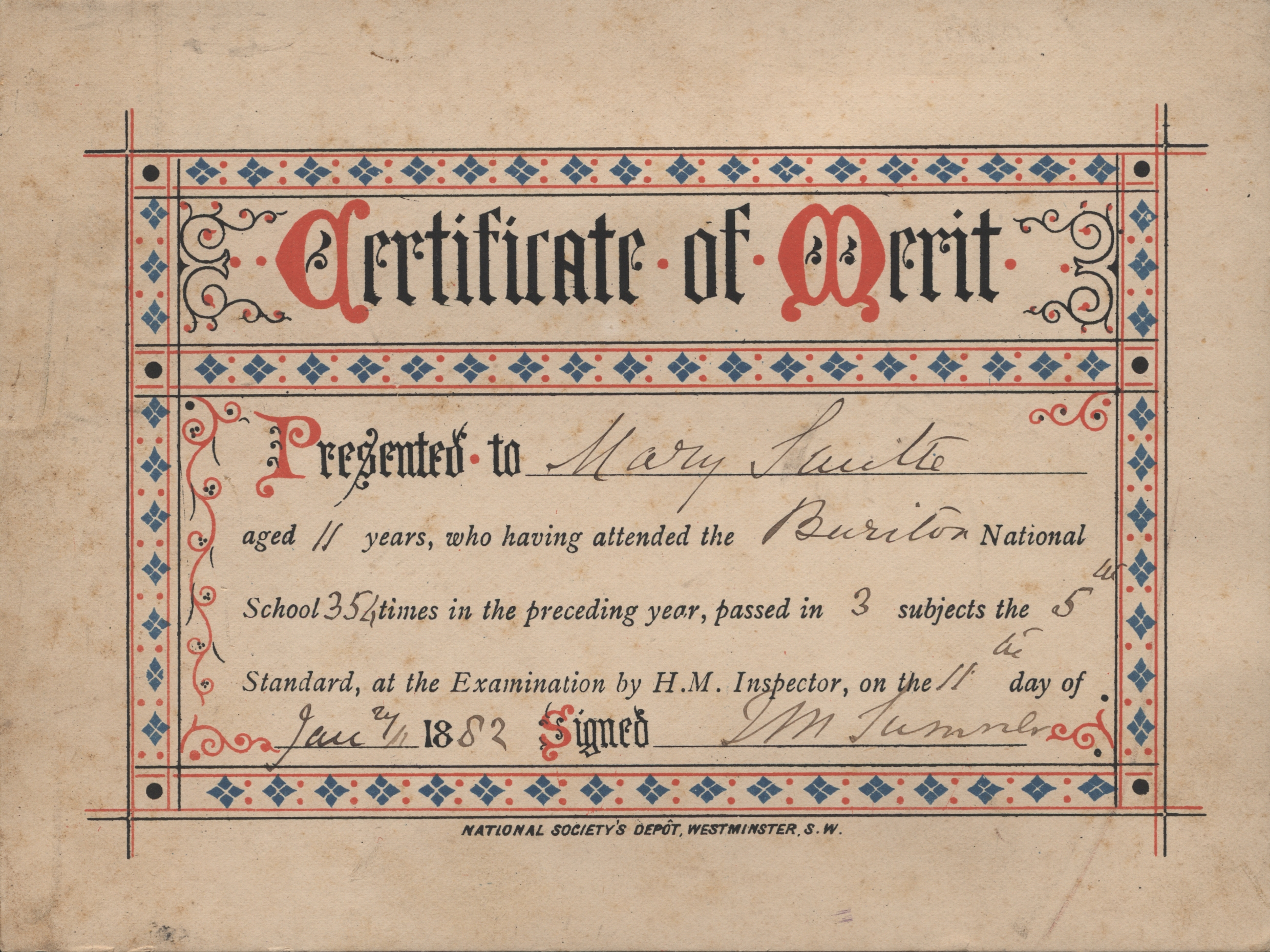

By May 1889, however, both Mr and Mrs Allison had resigned following a “Report of the Government Inspector of Schools which was decidedly unsatisfactory” and which resulted in no ‘merit grant’ whatsoever being given.

Mr Alfred Richard Patrick and his wife Helen Mary Patrick took over later that year and Miss Annie Maria Pitney was engaged as an assistant. In May 1891 an assistant called Minnie Irene Ralph (or Raft) is recorded and in 1895 there appear to be two assistants: May Smith and Kate Steadman. In June 1900 an assistant called Annie J Chappell is recorded.

Percy Legg was at school in the first decade of the twentieth century and recalled that Miss Budd was his infant teacher and that a Miss Masters helped the Patricks as an assistant teacher. “Miss Gwilliam, a welsh lady, took over from Miss Budd and lodged with us up at Dean Barn.

In April 1923 Mr Walter Sherwood became the third Headmaster of the school. Miss Kathleen Bessie Pleasant joined as an assistant Mistress around the same time.

Miss Pleasant was to be at the school for over 40 years. In conversation some time after she had retired she could still remember her first days at the school: she described herself as “essentially a country girl” and explained that she had been rather unhappy at a school in a large industrial city before she applied for the job in Buriton. She particularly remembered that two of the of the girls had decorated the top of a rather ugly cupboard with cowslips – “which was delightful to someone just coming to the country from a big city”. She explained that that was “the beginning of 40 very, very happy years” which meant so much to her.

Mr Sherwood left at the beginning of August 1928 having been appointed Head teacher of the Drayton County School. Mrs Violet Minnie May McDowell took over until 1st October when Miss Pleasant became headteacher (at a salary of £204-15s pa). Whereas both Mr Patrick and Mr Sherwood had lived in the school house next to the school, Miss Pleasant lived in a council house in Petersfield Road.

Locals who were taught by Miss Pleasant recall that they all used to look up to her as the figurehead of the school. She lived in Petersfield Road and kept bees, which she had ‘inherited’ from her uncle, in her back garden. Amongst many other things she is credited with initiating Christmas parties for the schoolchildren.

For much of the time that Miss Pleasant taught the seniors (ages 8-11), Miss Eva Coles taught the juniors (ages 5-7). Miss Coles was from Clanfield and used to drive to the village in a little old Morris Minor. She, and her pale green car, became part of the village life. Although she was described as “an atrocious driver”, she was also renowned as a very good teacher – “absolutely the right sort of person to teach juniors”. Miss Pleasant apparently complemented Miss Coles very well – “a bit more of a disciplinarian; but a very caring person”. Miss Digby was one of the extra teachers during the war time, using the Church Hall as a spare classroom.

Miss Pleasant retired in July 1966, having been at the school for over 43 years, and on September 1st Mrs V J Stone commenced duties as Head-mistress. A few years later, in December 1972, Miss Coles retired after 32 years at the school. Marjorie Wilcox was headmistress from 1974 to 1980 and describes this time as “happiness, warmth and fun”.

Other long serving members of staff have included Joan Knight who, after being a pupil at the school, became one of the first dinner ladies. Mrs Knight, whose mother, children and grand-children also attended the school, received a long service certificate for her time at the school.

More recently, headmaster Eric Hunt developed a strong musical tradition in the school. The school has always been interested in the production of concerts and entertainments and old school records, now stored in Winchester, contain details of programmes in which familiar names of generations of village families appear. Elderly residents can still remember school concerts, “packed full of people”.

This information was written in 2001.

Do you know any more about the history of the school, about school-days or about any of the teachers or staff who worked there?

Do you have any old photographs of the school or schoolchildren ?