After a bit of a dispute (see “The Battle of Havant” later on this page), trains started running on the line in January 1859. For the first twenty years it was a single track although the tunnel and all the bridges and earthworks had been built for double tracks. In 1878 the line was ‘doubled’. It was electrified in 1937 which, quite literally, sparked new life into the line, with regular and more frequent stopping and fast trains at higher average speeds.

The building of the railway line has made many differences to the village. In its early days it meant that coal could be brought to the area and the local limeworks could be established. This brought new employment and new families to the parish and the railway took away enormous amounts of lime for the building industry. Today, fast and frequent train services mean that people can live in Buriton but work many miles away in Portsmouth, Guildford, Woking and London.

For many years goods trains would call at Buriton Sidings every day. There used to be a ‘coal club’ for manual workers living in the parish. Two or three trucks of coal (at £1 per ton) would be ordered early in January and, when it arrived, a notice would be circulated round the village and the sexton would organise the distribution.

George ‘Sonner’ Legg can recall that “most of the materials for the school used to come in by rail into the sidings. A communal trolley was available at the Five Bells to help carry things into the village, down Kiln Lane. The library used to deliver a big crate of books every month and three boys would bring that down to the school. A goods train would come to the sidings every morning and you would get a note if there was something to be collected. You would then have two or three days to collect things; after that you were charged. You had to sign a book to say that you had received things – in a glass shed, supervised by the signalman.”

There used to be a number of houses along the side of the track for railway workers but these, and the signal box, were demolished in the 1960s and 70s.

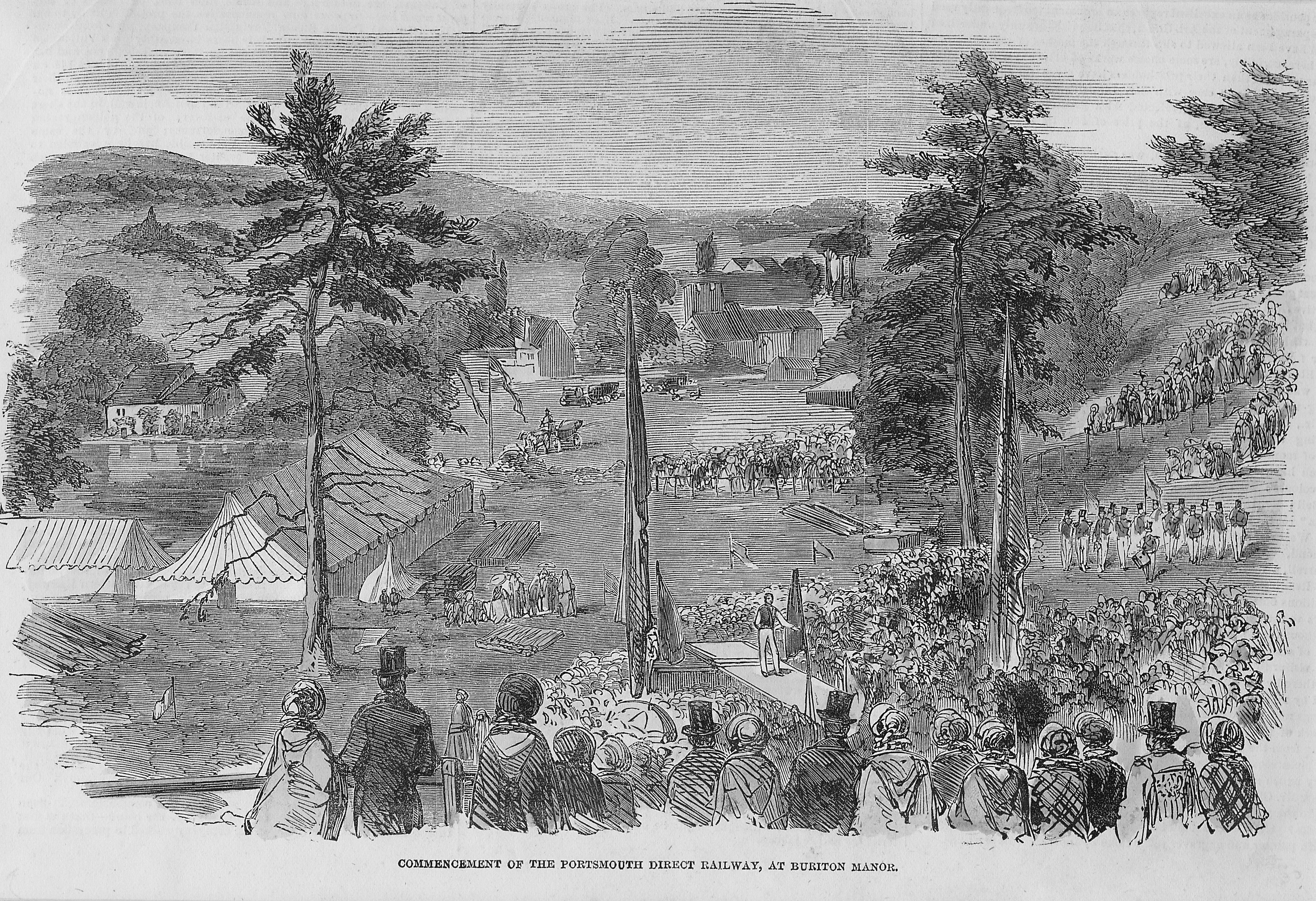

An article in the Illustrated London News of 13 August 1853 describes the commencement of the Portsmouth Direct Railway at Buriton Manor.

“To Mr Bonham Carter MP for Winchester was the graceful compliment paid of having the work begun on his land at Buriton near Petersfield and the first turf was cut by him on Saturday, August 6th 1853.

About 3.00pm a large party conveyed from London to Farnham by special train and from thence by other conveyances to Buriton about two miles south west of Petersfield. It is delightfully situated at the bottom of the northern slope of the South Down hills whose chalky downs are covered with a soft, deep, verdure and stately trees which cloth steep banks up to their summit.

It was in the very heart of the scenery thus commemorated by Gibbon from the face of the bank immediately in sight of his manor house that the first turf was to be cut. To this spot the company walked in procession from the house, preceded by the Royal Marines Band from Portsmouth. The hill itself was covered with some thousands of persons assembled from all parts of the country. When the procession came up, the various members in it had taken their places and silence had been obtained through Mr Harker, Mr Mowatt, the Chairman, addressed them on the advantages of railways and of the projected line.

Mr Errington, the engineer, also addressed the meeting and said that the line would require 100 bridges and that between 2,000 and 3,000 workmen would be employed on the work for two years. Mr Errington then handed a handsome silver spade, having the Arms of the company engraved on it with the date of the commencement of the undertaking, to Mr Bonham Carter who, casting off his coat in true workmanlike style, manfully wielded both spade and pickaxe and speedily filled a handsome mahogany barrow with the turf intermixed with bouquets of flowers which were flung in by the ladies and then wheeled it along some planking and tipped it over into the bottom amid the cheers of the spectators.

He then addressed the audience in his working costume and after some graceful remarks on the pain which it gave him to be instrumental in breaking up and injuring the seam of soft and silken beauty which spread around, he added that he was sure that regret would be but for a short time while utility and the convenience would be permanent. It would benefit the district through which it passed; it would facilitate the intercourse between the coast and the metropolis; and from the interest the Government has manifested in the undertaking, he believed it would strengthen the defences of the country. For these reasons he had himself done what he could to forward the interests of the line and he now wished it and its directors every success.

The ceremony of the day was now concluded, the company filed off the ground and left the spot to the operations of the workmen who, setting to their work with a will, had opened a deep wide cutting in the breast of the hill. While they were plying spade and mattock, the Chairman and Directors, attended by the invited guests, proceeded to a marquee which had been provided by Mr Crafts of Petersfield. Mr Mowatt presided. After the loyal and patriotic toasts and after drinking to the success of the undertaking which had that day so auspiciously commenced, the party broke up and returned to town by way of the South Western Railway.”