Most visitors to Hampshire are aware of Jane Austen’s cottage at Chawton and of Gilbert White’s house, The Wakes, at Selborne. But there are other people – equally deserving of homage – whose names are largely forgotten, even by local people. This note provides some details about three ‘local luminaries’: Edward Gibbon, John Goodyer and the Bonham Carters.

Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon, author of the classic “Decline and fall of the Roman Empire”, among other works, lived at Buriton Manor for much of the second half of the eighteenth century.The manor and the estate were owned by the Gibbon family from about 1719 to 1789. Edward Gibbon I (the historian’s grandfather) is believed to have bought the Manor of Buriton at the same time as the Borough of Petersfield in 1719, shortly before the South Sea Bubble, of which he was a director, burst. This involved him, and the other directors of the Company, in the forfeiture of the greater proportion of their private property. Possession of Buriton was, however, confirmed to him by the Trustees of the Company in 1724. It was probably this Edward who planned the Georgian wing and converted “an old mansion in a state of decay … into the fashion and convenience of a modern house.” Where the original house, built of stone, ended and the elegant Gibbon addition began can still clearly be distinguished today.

Edward Gibbon I died in 1736, and the Manor passed to his son Edward, the father of the historian. The family appear to have neglected Buriton, however, until at least 1747 – preferring their larger house in Putney and the closer attractions of London society.

Edward Gibbon III, the historian, was born in Putney in 1737 – the eldest of a string of brothers, all of whom died in the cradle having successively been christened Edward to ensure continuation of a favourite family name. After the death – in childbirth – of Edward’s mother in 1747, his distraught father buried himself in the Hampshire countryside and Edward was brought up by his aunt, Catherine Porten.

His life in Buriton

He was a sickly, nervous, child and many of his early days were spent taking the waters at Bath and acting as a guinea-pig for doctors in Winchester. Edward had to be taken away from Westminster school because of poor health and, when the efforts of physician’s failed to cure him, he was prepared for Oxford by a private tutor. Having survived childhood, he went to Magdalen College in 1752. Here, however, his memoirs suggest that he received neither instruction nor companionship, finding the boys frivolous, the dons indolent and his fourteen months there to be “the most idle and unprofitable” of his whole life.

That he only spent fourteen months at the University was due to the fact that his father expelled him (still only aged 16) to Lausanne as soon as he learnt that young Edward had become converted to Catholicism. Switzerland was a hotbed of Protestantism and, under the tutelage of a Calvanist Minister, M. Pavilliard, Edward repudiated his Catholicism and followed a carefully supervised programme of studies with particular emphasis on the French and Latin classics and the mastery of these languages. He returned to England after six years as a member of the established church and it is from this date, 1758, that his close association with Buriton began. He lived here, apart from his travels abroad, until his father died in 1770 and he moved to London in 1772.

His arrival in Buriton produced something of a shock for him, as his father had remarried in his absence, and “I considered his second marriage as an act of displeasure, and I was disposed to hate the rival of my mother.” But the new Mrs. Gibbon, who had been Dorothea Patton, gradually dispelled her step-son’s suspicions and a fairly good friendship developed.

The family appear to have been popular in the neighbourhood, despite their long absences in the past. Edward’s father had been elected MP for Petersfield in 1734 and as a Tory and High Churchman had been in sympathy with the majority of local gentry who had little time for the ostentatious Whig party, epitomised in Sir Robert Walpole, who had run the country, in effect, since the turn of the century.

“Our immediate neighbourhood (at Buriton) was rare and rustic,” wrote Gibbon, “but interspersed with hospitable families, with whom we cultivated a friendly, and might have enjoyed a very frequent, intercourse.” Although not a countryman at heart, Gibbon enjoyed the solitude of Buriton, and left a valuable account of life at the old manor :

“My father kept in his own hands the whole of the estate, and even rented some additional land; and whatsoever might be the balance of profit and loss, the farm supplied him with amusement and plenty.

“The produce maintained a number of men and horses, which were multiplied by the intermixture of domestic and rural servants; and in the intervals of labour the favourite team, a handsome set of bays or greys, was harnessed to the coach. The economy of the house was regulated by the taste and prudence of Mrs. Gibbon and I was transported to the daily neatness and luxury of an English table.

“The comforts of my retirement did not depend on the ordinary pleasures of the country. My father could never inspire me with his love and knowledge of farming. I never handled a gun, I seldom mounted a horse; and my philosophic walks were soon terminated by a shady bench, where I was long detained by the sedentary amusement of reading or meditation.

“At home I occupied a pleasant and spacious apartment; the library on the same floor was soon considered as my peculiar domain; and I might say with truth that I was never less alone than when by myself.”

“The aspect of the adjacent grounds was various and cheerful: the Downs commanded the prospect of the sea, and the long hanging woods in sight of the house could not perhaps have been improved by art or expense.”

We can probably picture Gibbon, his father and his step-mother driving out through the village behind their ‘favourite team’ to visit the Jolliffes at Petersfield, the Stuarts at Hartley Mauditt or the Butlers at Liphook, all typical country gentry of the period. Perhaps a little too inclined to fox hunting for Edward’s taste, but nevertheless a carefree, jovial society.

His only real complaint at this time concerned the demands made on his time by his parents. After breakfast his stepmother expected his company in her dressing room; after tea he had to join his father for conversation and “the perusal of the newspapers”. And often when he was deep in a learned folio he would be called down “to receive the visit of some idle neighbours,” which in due season required a similar return. Edward learnt to dread the time of the full moon which was usually reserved for the family’s excursions to more distant neighbours for tedious dinner parties.

In 1759, when he had begun to seriously consider writing as a career, Edward and his father volunteered for the Hampshire regiment. England was engaged in the Seven Years’ war with the French and father and son were commissioned respectively as captain and major. “We had not supposed”, he complained, “that we should be dragged away, my father from his farm, myself from my books, and condemned during two and a half years to a wandering life of military servitude.” He disliked military life and the cold discomfort of camps on the Hampshire coast, and it was not until 1762 that he could enjoy “at Buriton two or three months of literary repose.”

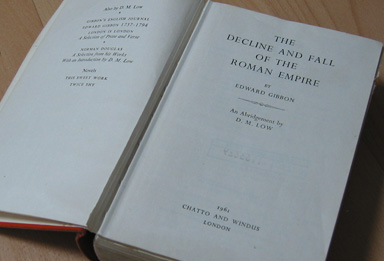

Although he was to serve in the Hampshire militia until 1770, rising gradually to the rank of lieutenant-colonel commandant, he also found time to embark on a long-projected tour of Europe. In 1761 he completed his first work, in French, ‘Essay on the Study of Literature’, in defence of classical studies. But, as his memoirs record, “It was in Rome on the fifteenth of October, 1764, as I sat musing amidst the ruins of the Capitol, while the bare-footed friars were singing vespers in the Temple of Jupiter, that the idea of writing the decline and fall of the city first started in my mind”. He was 27 at the time and it was over 20 years later that he completed his task.

In 1770, following the death of his father, Edward resigned his commission in the Militia. By this time he was dividing his time between the family home in Buriton and the fashionable clubs of London. His membership in Johnson’s literary club was an annoyance to Boswell, who described him as “an ugly, affected, disgusting fellow.” Others, too, remarked on his features which have been compared to a potato. But, in the words of one his more modern biographers – E J Oliver – we could not fail to notice that the large button of a nose, which had drawn in such quantities of snuff, “had the sensitive precision of a terrier’s in extracting the bone of a fact from the ash-heap of history”.

In 1772 he moved to London and applied himself to his life work. Although Buriton saw him from time to time, the lure of society – and the London bookshops – proved more attractive. It was not, however, until April 1789 that he sold the manor and the estate to Lord Stawell.

He was elected to the House of Commons in 1774, held his seat for eight parliamentary sessions, but did not speak once. He did not, however, consider this time to be wasted. These years were “a school of civic prudence, the first and most essential virtue of an historian”.

The first volume of Decline and Fall was published in 1776 and was immediately acclaimed as a classic. Volumes II and III which were published shortly afterwards were received more quietly. From 1779 to 1782 Gibbon served on the Board of Trade which added to his income. But, soon after the Board was dissolved, Gibbon also lost his seat in Parliament and it became impossible for him to maintain himself in London.

In 1783 he moved to live in Lausanne (with his life-long friend, George Deyverdun) where he remained until a few months before his death. Here the last three volumes of his work reached rapid completion. “It was on the night of the 27th of June, 1787”, he recorded “between the hours of 11 and 12 that I wrote the last line of the last page in a summer-house in my garden…. I will not dissemble from the first emotions of joy on the recovery of my freedom and, perhaps, the establishment of my fame. But my pride was soon humbled, and a sober melancholy was spread over my mind by the idea that I had taken an everlasting leave of an old and agreeable companion, and that whatsoever might be the future fate of my history, the life of the historian must be short and precarious.”

It was, in fact, only seven years later when he died at his house in St James Street, London, on 16 January 1794. He had moved back to London in 1793 after the death of his friend Deyverdun in 1789. He had been suffering for some time from dropsy and gout and, upon his return, underwent a number of operations. He died in his 57th year and was buried at Fletching in Sussex.

Over the years, Buriton Manor had seen, as guests, many of the leading literary figures of the day, from Dr Johnson to Adam Smith, Chesterfield to Sheridan. Many of Gibbons’ early Essays were composed here. Although little, if any, of the ‘Decline and Fall’ was written at Buriton, germs of the work may well have been conceived here in his father’s library, or while strolling in the meadows or the woods nearby.

John Goodyer

John Goodyer, one of Britain’s greatest botanists, lies in Buriton churchyard in an unmarked grave. He was building up botanical knowledge a century before Gilbert White. He was born in Alton in 1592 and appears to have had a good education. He lived for quite a time at Droxford although from about 1616 he was working in this parish as a steward or an agent for Sir Thomas Bilson of West Mapledurham House (a large manor, about a mile north-north-west of Buriton village, which was demolished in 1829).

By 1631 he was living in the parish – at Mapledurham – and his letters and notes (many of which are stored at Magdalen College, Oxford) show that he was stocking and planting a new garden here as he had done in Droxford. After his marriage in 1632 he moved to the house that today carries his name in The Spain, Petersfield.

How long Goodyer worked for Sir Thomas Bilson is unclear but it is known that he sometimes had to visit neighbouring towns and outlying farms and even to ride up to London on his master’s business. Botany was his hobby and his miscellaneous papers show that even while he was occupied with the business of estate management, or of the Courts, or in dealings with tithing officers, his mind would always be turning to the plants which he had seen in the gardens of his friends or had found on his excursions. He was in the habit of jotting down lists of plants and odd notes on the backs and covers of letters, on petitions, or on any stray scrap of paper that came to hand. This has helped people to date his botanical notes, but it means that names of plants are intermingled with figures of calculations, notes for his excursions, medical prescriptions, names of litigants and taxpayers, and even shopping lists !

Over the years Goodyer discovered and described many, many plants new to the British flora. He received plants and seeds from other gardening friends and grew them in his garden, describing them in detail when they flowered. He made a number of significant botanical discoveries, including clarifying the four principal types of British elm tree, and was described by one contemporary as “The ablest Herbarist now living in England”. Another noted that “Hee hath an excellent Garden and all kinds of Exotick Plants.”

Perhaps his most widely known claim to fame is the introduction of the Jerusalem Artichoke to English gardens and cookery – and his oft-quoted description of ‘its virtues’:

“Which way so ever they be dressed and eaten, they stir and cause a filthy loathsome, stinking wind within the body, thereby causing the belly to be pained and tormented,

and are a meat more fit for swine than men.”

It was 1617 when Goodyer received “two small rootes” of these artichokes from a gardening friend in London, John Franqueville. At this time he was probably still living in Droxford and so it is to that village, rather than to Buriton, that the honour of having been the first place in England to produce the new Artichokes in quantity must go. Perhaps, given his vivid description of ‘its virtues’, we are not too upset about losing that honour ?

Goodyer collaborated with Thomas Johnstone in correcting and enlarging the greatest ‘herbal’ of the previous century – the “Gerard Herbal”. This second edition became known as the “Emmaculate Gerard Herbal” and was the standard work in English on botany, beautifully illustrated and crammed with careful research. He also translated some of the major european works on botany into english – perhaps his greatest one being the translation of the 4540 page “Materia Medica”, written by Dioscorides, from greek into english.

John Goodyer died in the spring of 1664 and was buried, as he directed in his will, in Buriton Churchyard near his late wife. He left all his books, manuscripts and notes (one of the most valuable botanical libraries in the country) to Magdelen College. Most of his property was left to his heir and nephew the Rev Edmund Yalden except his house and garden in The Spain and two fields to the west of the Causeway named the Halfpenny land. He bequeathed that the house and this land be rented out and that the income raised be used as a charity for the poorest inhabitants of Weston and to help young children of the area on their way in life.

Many were helped by being placed as apprentices: the first, in July 1665, being Thomas Wise of Weston who learnt a trade with Thomas Matthews, a wheelwright in Buriton. In a typical year there would be one or more apprentices placed and fourteen or so poor families helped with some money at Christmas or midsummer. Not all the apprentices were boys, for in April 1673 Hannah, daughter of William Cox of Weston, was placed with Anne Legge of Petersfield, widow, ‘to work her the trade of a seamstress’. The John Goodyer Charity still exists today and its Trustees continue to carry out the spirit of his intentions.

The Bonham Carter family

The Bonham Carter family, long involved in politics, trade and service to the country, owned the Buriton estate for about 130 years. Their double-barrelled surname did not come from a marriage, but had its origins in a pub – or, more accurately, in brewing.

Pike’s Brewery, which was founded in 1719 (subsequently taken over by Brickwoods in 1911 and, in turn, by Whitbread’s in 1973), was owned by William Pike. He died in 1777 and the responsibility for the brewery passed to his two daughters: Ann and Susanna. Ann (1716-1787) had married John Bonham (1705-1771) and Susanna (1737-1761) had married John Carter II (1715-1794) – a portent of the coming joint family name.

The Bonhams and the Carters were both prominent families in the county. The Bonhams were landowners in Hampshire, living in Warnford and West Meon since the seventeenth century (and before that in Wiltshire). The Carters were a prominent Portsmouth family They had lived there as early as the sixteenth century. John Carter I lived from 1672 to 1732 and was a shipwright, timber merchant and a burgess of Portsmouth. His son John, who married Susanna Pike, was mayor of Portsmouth seven times.

John Bonham married Ann Pike in 1747 and they lived in Castle House in Petersfield Market Square (where the Post Office is now). They had four children but neither of the two boys (Henry: 1749-1800 and Thomas: 1754-1826) ever married and the two daughters produced no heirs. Thomas managed the brewery for some years but it was Henry who bought the Buriton Estate in 1798 from Lord Stawell who had bought it from the historian Edward Gibbon.

Susanna’s husband, John Carter II, also managed the brewery for a time and, in his turn, so did their son John Carter III (John and Susanna had four other children). John III (1741-1808), who was knighted by George III, had six children, the only son being named, again, John.

It was this John Carter (John Carter IV; 1788-1838) who, in the absence of any heirs in the Bonham family, inherited an estate of several thousand acres around Buriton, Petersfield and West Meon in 1826. On 17 February 1827 he changed his name by Royal License to John Bonham Carter I to testify his “esteem and regard” for his late cousin. And thus we move into the Bonham Carter dynasty.

John Bonham Carter I never lived at Buriton. He married Joanna Smith and they raised their family at Castle House in Petersfield but, as he was MP for Portsmouth for over twenty years (1816-1838), they often preferred to live in Westminster to be near Parliament. John and Joanna had ten children but, again, none lived at Buriton Manor. Their eldest, John Bonham Carter II (Jack), followed his father into politics becoming MP for Winchester and a junior minister in the first Gladstone administration. He and his family lived briefly at Castle House but, in 1858, they built an impressive mansion at Adhurst St Mary, Sheet. Jack had nine children and when he died in 1884 his heir was his son John Bonham Carter III. He died in 1905 and the Buriton estate then passed to Jack’s other son Lothian.

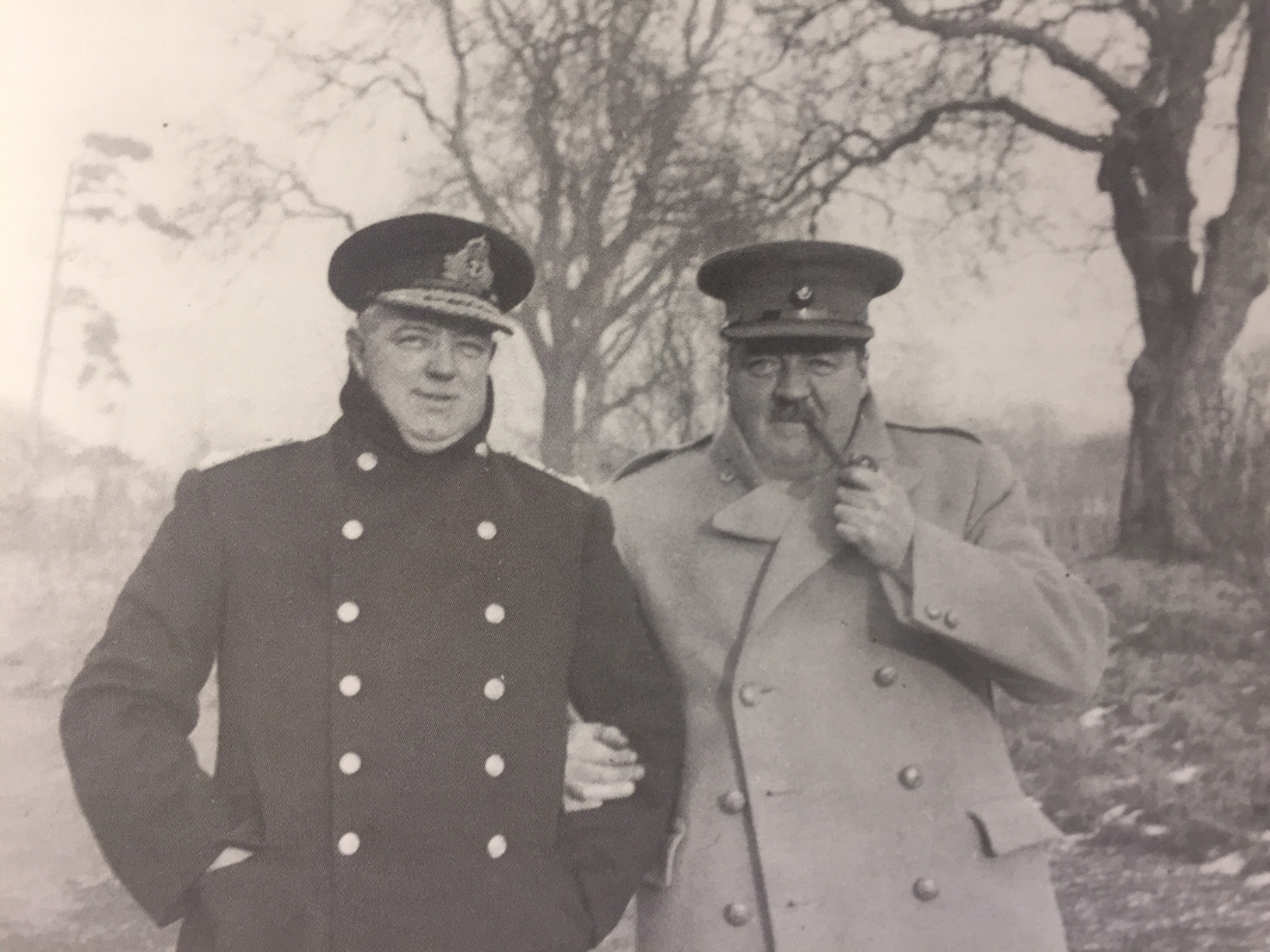

Lothian Bonham Carter (1858-1927), grandson of John Bonham Carter I, was the first to live in Buriton. He had Buriton House built in about 1910/1911 as his wife reputedly did not like living in the Manor House which was, in those days, still a working farm. Lothian had two sons, Colonel A L (Algernon Lothian) Bonham Carter DSO (born 1888) and Admiral Sir Stuart Bonham Carter (born 1889), and a daughter who became Mrs Tomlinson.

As well as running the Manor Farm with its renowned hop cultivation and regular pheasant and rabbit shoots, the family also had a prolific sporting reputation. Lothian Bonham Carter played cricket for Hampshire and his uncle Henry and aunt Sibella had twelve children, eleven of them boys – enough to field a cricket team; which is exactly what they did !

The Bonham Carter XI, or The Old Caravan, as it was picturesquely known, flourished during the latter part of the 19th century. By the turn of the century, three of the brothers had been replaced by younger Bonham Carter cousins (including Lothian), but they were still very much a force to be reckoned with. On one memorable occasion in the early 1900s they beat Petersfield by 96 runs. A local newspaper report records that Lothian opened the batting and scored 54. The team reached a total of 261 and then dismissed Petersfield for 165. The Bonham Carter scorers were : Lothian 54, Charles 20, Norman 17, Octavius 81 (not out), Reginald 4, John 37, Edgar 22, Maurice 3, Walter 0, Frederick 1, Alfred 0 (with 22 extras).

Lothian died in 1925 and the Buriton estate passed to his son Algernon although large tracts of downland were taken over by the Forestry Commission in 1927 to cover death duties. Algie, ‘the Colonel’, loved the centuries old Manor House and spent time restoring and renovating it. He sold Buriton House. The rest of the estate was sold after he died in 1957. The Colonel is remembered as “a lovely man”. He was cremated and his ashes spread in Pillmead Covers by his brother Admiral Sir Stuart and his Head Gamekeeper George Legg senior.

Vice Admiral Sir Stuart S Bonham Carter KCB, CVO, DSO died at the age of 83. He had served with distinction in action in both world wars. In 1918 he was among the volunteers selected to take part in the raid on Zeebrugge on St George’s day. In this operation he was in charge of the blockship Intrepid, which he successfully sank in the Bruges canal, escaping with another officer and four petty officers in a Carley raft to be picked up later by a motor launch. Mary Piggott, who died in 1998, recalls that when the Admiral came back after Zeebrugge, all the schoolchildren were marched up to Buriton House and lined both sides of the entrance. All had flags and sang ‘Heart of Oak’. Apparently the Admiral was so tired that he probably couldn’t have cared less about anybody and just went straight past into the house!

Florence Nightingale was a relative of the Bonham Carter family with the connection going back to John Bonham Carter I. Helena Bonham Carter, the famous actress, is the great, great granddaughter of John Bonham Carter I. Her grandfather was Maurice who played in the cricket match against Petersfield but only scored 3 runs. So, whilst none of the famous females appear to be directly connected to Buriton, at least we had one of the best cricketers !