Range of crafts and skills

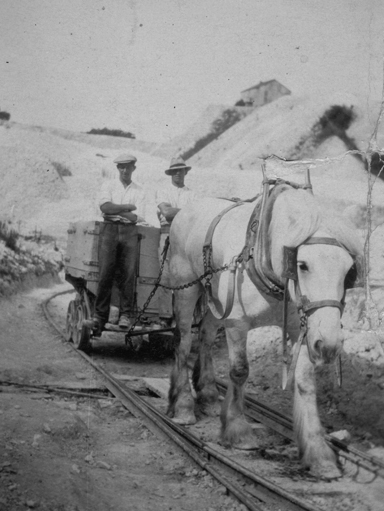

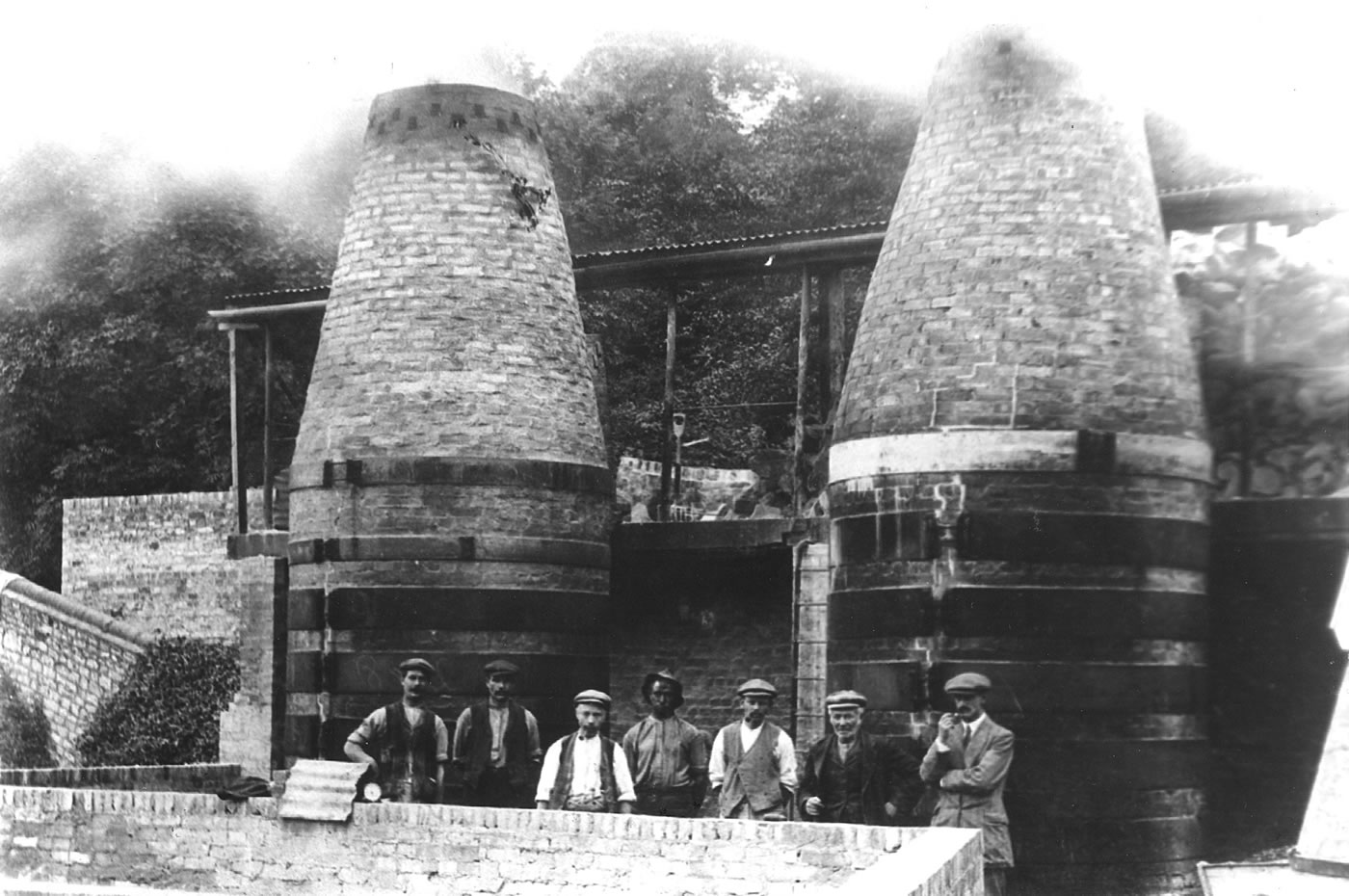

The limeworks employed about 40 people (possibly nearer 100 in the summer months when there was a greater demand for lime from the building industry) with a wide range of crafts and skills. Jack Nicholson used to look after the horses and the limeworks had their own granary to store oats for their feed. Underneath the granary was Charlie Morris’s carpenter’s workshop. All the wooden 3ft gauge trucks for the internal railway were built and repaired in this shop. Beyond the carpenter’s workshop was Freddie Tussler’s blacksmith’s shop and the works also had their own bricklayer, Tipney Welch, and a sail-maker to make tarpaulins to cover the lime in the railway trucks (Joe Hall’s father).

The limeworks office, where George Shand worked, was the northern (original) part of the two low, tiled sheds now in the back garden of Swiss Cottage. Between them and the railway line is the old stables building and closer still to the line was the sack mending shed where Mrs Burgess and Mrs Hall worked. A little further towards the railway tunnel was the stores building which had “Forders Lime Works” painted in white on the tarred galvanised iron roof facing the tracks.

Other employees in the latter years of the limeworks, mostly members of the gangs that worked in the quarry pits or chalk-burners, included Slide Pretty, Curly Pretty, Nobby Pretty, Harry Tussler, Henry Albury, Shucky Marriner, Kronjie Hall, Joe Hall, Titch Barrow, Neddy Lee, Albert Hall, Charlie Hall and Jack Haynes. Jack Carter was in charge of the diesel engine that ground the lime and his father, Sidney Carter, was the manager of the works (after a Mr Henry Wyril Posgate) and lived in the White House in the High Street.

Do you know any more about any of the workers at the limeworks?

Each man had a key to clock on at the ‘Bundy’ clock which recorded the time. The ‘skilly’ bell was rung at 12 noon, the start of the lunch break, and again at 1 pm. On wet days, the pony boys responsible for the horses and the men who worked on the gangs in the pits would get coated in chalk. At the end of such days, when they got home, they would probably have to take their clothes off outside in a shed. And you could always tell if they had popped into The Maple at lunchtimes for their Woodbines – there would be a white trail across the floor from the door to the bar !

Effects on village life

As Percy Legg (1896-1981) recalled in the 1960s, “the closing down of the limeworks made a lot of difference to the village. It employed 40 men. I remember seeing them come home from work for lunch like men leaving a factory”. At the end of each day, the horses would be ridden, bare-back, down Kiln Lane and through the High Street by the pony boys to be washed in the village pond. They would then race back to the limeworks – an exciting sight for the village children.

The village cricket team drew heavily on employees from the limeworks. With at least 40 men at the limeworks and probably another 50 men working on the farm and the estate, there were lots of good players to choose from. Apparently, the season often started with a match between the limeworks and the men from the farm and the estate.

The tall ‘shaft’ was demolished on August 14th 1948 after being up for about 70 years. On Queen Victoria’s Jubilee in 1887, one of the limeworkers, Charlie Fisher, is reported to have climbed the 145ft chimney for a 6d wager. Apparently, he was not paid his sixpence but was later stood a beer (costing 2d). This seemed to rankle with him.

The chimney was demolished under the supervision of Jim Winser of Weston Farm and his business partner, a Mr Sykes from Froxfield. They had bought the limeworks and had decided that the shaft was dangerous. All the estimates of costs that they obtained were rather high because of insurance to cover the risk of anything affecting the nearby railway. They therefore decided to demolish the chimney themselves – and formed a £100 company (Winser and Sykes, Demolition Limited) which would have put an upper limit on any compensation the railway company could obtain. They thereby avoided the need for insurance !

The men had not demolished anything like that before – not many people had. To demolish the chimney, some of the bricks at the base were replaced with railway sleepers, which were surrounded by wood and set alight. When the sleepers eventually burned, the chimney fell “in exactly the right place” and broke up on a series of telephone poles which had been laid out on the ground. This meant that many of the bricks were cleaned, ready for re-use. It is reported that a local cricket match was halted (for “ten minutes” or “nearly an hour”) while players watched.

More recent uses

During the second world war the ‘France’ pit was used for steaming out (and sometimes detonating) land mines. More recently it was filled with refuse. The ‘White’ pit was later occupied by Buriton Sawmills. It is still possible to walk through the ‘Germany’ pit and old sleepers can be seen. After the Admiralty had finished with the main works site in ‘Germany’, George Andrews took it over and used it as a scrap yard. After this Winser’s used the site for making bread and more recently Cemco took over. The remains of any kilns have been buried, but several buildings survive, including the mill, granary and carpenter’s shop, limeworks office and stables. There have recently been proposals to designate part of the site as a nature reserve.

And down the hill the limeworks stood,

Where men worked by the score,

But now cement has come to stay

And lime is used no more;

The pits are muttered in you see

And form a rubbish tip.

The kilns and shafts are all knocked down,

It’s hard to notice it.

[extract from one of Percy Legg’s poems, c1964]