Today, most of us take relatively smooth, tarmac roads for granted. We can get to most places that we want to quite quickly and quite comfortably. We think of the nearby A3 simply as a fast and convenient way to get to Portsmouth, Guildford or London. Yet, only a century or so ago, most of our local roads were very rough – made of chalk and flints. And the A3, the renowned Great Portsmouth Road, which runs through the heart of the parish has a history of danger and adventure – including smugglers, murderers and highwaymen.

Local Roads

Most of our local roads have only been properly surfaced in relatively recent times. Most used to be made up of chalk and flints. Piles of broken flints were kept by the side of the road to fill the ruts. Cyril Fullick, who died in 1977 at the age of 90, recalled that farm workers used to have to collect flints from the Downs during the winter months. These were broken up and what was not used on the farm was sold to the council. They were measured by piling the flints into wooden frames with a handle at each end – this represented half a yard with a yard being about a ton. Gypsies would come to do a day’s work on the piles of flints to break them up. There was a pile kept outside Corner Cottage and others elsewhere around the village. The gypsy would sit all day with a short-handled rake in his left hand drawing the flints towards him and a hammer in his right to break up the flints.

The Milky Way was used by residents of Coulters Dean to get to market and it was also used by the Cave family when they lived at Ditcham House. They helped to put flints into it to try to create a hard surface. Back at the end of the seventeenth century, Celia Fiennes had written about her journeys to visit an aunt who lived at Nursted House saying that “the roades all about this country are very stony, narrow and steep hills, or else very dirty …”. In more recent years the village had a local road maintenance man who kept the Milky Way in order on Saturday mornings and who also swept along the High Street and round by the church. Apparently, everywhere was quite a bit cleaner and tidier than it often is today !

There are recollections that the High Street and North Lane used to be tarred, just with sand – no chippings, for many years. But as there was very little motor traffic this surface was quite adequate and for some roads – particularly Hall’s Hill – a rough flint surface was better so that all the horses could get a grip. Carts and wagons coming down the hill with their ‘shoe brakes’ on would drag up the flints. It doesn’t seem as though Hall’s Hill was surfaced until sometime after World War Two and Percy Legg (1896-1981) recalled that Bones Lane was not done properly until about 1964. After a frost, the flinty/chalky roads were easily churned up by horses and carts. Sonner Legg recalls that it could be just like walking on porridge !

Even when Hall’s Hill was surfaced, the first motor cars would barely be powerful enough to get up the hill and many would get stuck. Sonner Legg can remember that local boys would often try to be thereabouts on a Sunday to maybe get a penny or tuppence for helping to push. Scrambling up Wardown to count the cars passing through Butser cutting or to note down their number plates was also a common pastime for young boys. Families, too, would take a Sunday treat of a walk up Wardown to watch out for motor cars coming along the road. And, of course, traffic on the Great Portsmouth Road (now the A3) has always passed through the heart of the parish.

The Great Portsmouth – London Road

In the days before metalled roads, or even turnpikes were established, Buriton was on the main London-Portsmouth Road. Its narrow streets would have rung to the clatter of many a horses’ hooves because the village presented an oasis in a desert of rough tracks and moorland with the then dangerous Forest of Bere, inhabited by highwaymen and robbers, lurking ominously nearby. From Buriton, guides would take travellers through the forest to Portsdown and on their way to Portsmouth.

In practice, there was probably a network of routes southwards from Petersfield. Some 17th century maps show the main road going via Nursted to Buriton from where travellers could aim for Finchdean or go along Buriton hanger to Gravel Bottom (through what is now the Country Park). Other maps show the road travelling south along the wet causeway and then up to a saddle between Butser Hill and Wardown. There was probably no hard and fast route before the present road was built – it would be a matter of choice, depending on the time of year, the weather, the traveller’s form of transport and his fear of the Forest of Bere.

In those days, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, road repairs were the responsibility of parish councils. Under the Highways Act of 1555, parishioners were required to provide labour, tools, horses and carts for four days each year, under the direction of a ‘Surveyor’ appointed by the Parish Churchwardens. All work was compulsory and no wages were paid, not even to the supervisory ‘Surveyor’. From the outset, this system seems to have been rather ineffectual. The local ‘Surveyors’ probably had little idea about how to repair roads and the idea of compulsory unpaid work was so unpopular that many parishes were taken to court for failing to perform their statutory duties.

In the mid-sixteenth century when wheeled traffic was infrequent (and mostly local) the failures of this system may not have caused too many problems. But as the amount of wheeled traffic grew during the seventeenth century, the weaknesses became more noticeable – particularly on the more heavily trafficked main roads. The growth of Portsmouth undoubtedly led to an increase of traffic on the main road to London and to serious problems just south of Petersfield where the road climbed sharply up Butser Hill.

Records show that the three villages responsible for repairing the road at this point (Weston, Buriton and Nursted) were finding it increasingly difficult to keep the road repaired. In 1692, the Justices of the Peace, under a power granted to them by the Highways Act of the previous year, ordered a 2d rate to be levied on the village of Nursted for road repair, and in the same year a 4d rate was imposed on Buriton and Weston. In 1693 Buriton had to raise a 6d rate with the proceeds “.. to be forthw’th applyed to ye repairing the aforesy’d highway leading from forebridge (in Petersfield) to Butsworth (ie Butser) hill being part of the road leading from Petersfield to Portsmouth”. Although the Justices caused rates to be levied elsewhere in the county, nowhere was the incidence of the rates as frequent as on the Butser Hill road.

This situation led to one of the first Turnpikes in the country being established through the parish in 1711. A petition to Parliament in 1706 explained that “… the Road, leading from Petersfield to Butsor Hill, in the Parish of Buriton, and Tything of Weston, in the great Road from London to Portsmouth, are becoming very ruinous, by reason of the many Loads, weekly passing them, of her Majesty’s Stores; and the Statute Works, and the Inhabitants, are not sufficient to repair the same: And praying that Leave may be given to bring in a Bill for repairing the said Road from Petersfield to Butsor Hill”. This petition was unsuccessful, but in 1710 another was presented which pointed out that this stretch of road was “almost impassable for at least Nine Months in every Year”. It is clear from both these petitions that the promoters were probably less concerned with providing better transport than they were with transferring the burden of repair costs to the road users.

One of the first Turnpikes in the country

The second petition to Parliament was successful and, when the Portsmouth and Sheet Turnpike Act was passed in 1711 (creating the Portsmouth and Sheet Turnpike Trust), there were only fifteen other turnpike authorities in existence in the country. The entire road between Petersfield and Portsmouth was covered by the Act and tolls could be collected from road users to pay for the maintenance of the road. The control of the turnpike authority was placed in the hands of a number of selected trustees: men of local importance such as town officials, professional men, merchants, landowners, Justices of the Peace and MPs.

The collection of tolls gave rise to considerable problems for most turnpike trusts. There were usually quite complicated arrangements for the charges to be levied. There could be limits on weights carried, the number of horses used and the breadth of wheels. Concessions were often granted to certain road users such as local churchgoers on Sundays, funerals, carriages during elections, the post, the military, carts with agricultural implements or with manure or with goods not going to market. Initial charges on the local turnpike included: “For every horse One Penny; For every Stage or Coach drawn by four or more horses One Shilling; For every Coach drawn by one or two horses Sixpence; For every Waggon with four wheels drawn by five or more horses One Shilling; For every other Cart or Waggon Sixpence; For every score of oxen or cattle Ten Pence; For every score of sheep or lambs Five pence; For every score of hogs Five pence”.

The Turnpike Trustees had to appoint gate-keepers responsible for interpreting the complex regulations and collecting the tolls. The complicated charging arrangements made it difficult to devise any effective check on the receipts collected and fraud by the gate-keepers was common. But it wasn’t necessarily a good life being a gate-keeper as they were often attacked and assaulted by travellers who were refusing to pay. To many people, the Turnpike Trusts seemed to be little more than a new tax, removing the right of passage on the king’s highway.

The turnpike trusts were established so that the roads could be better repaired, but most of the trustees probably had very little knowledge about how to go about this – and there was very little technology or experience to draw on. Most trusts repaired their roads by filling in ruts and covering the road surface with stone, gravel or other materials. Although many records from the Portsmouth and Sheet Turnpike Trust survive, they give few details about repairs. The accounts suggest that large quantities of gravel, stone and chalk were used on the road, that contracts were made with local farmers and that women as well as men were hired to gather loads of stones. Most road labourers were probably local people who were employed in agriculture when not working on the roads. Local records show that in the 1720s they were paid 1s 3d (about 8p) per day to work on the road.

In ‘Nicholas Nickleby’, Charles Dickens describes the walk up the hill over Butser where “there shot up, almost perpendicularly into the sky, a height so steep as to be hardly accessible to any but the sheep and goats that fed upon its sides…”. Once Nicholas and Smike were over the hill “twilight had already closed in, when they turned off the path to the door of a roadside inn, yet twelve miles short of Portsmouth”. This roadside inn was the Coach & Horses or Bottom Inn which still stands near the Queen Elizabeth Country Park Information Centre. A more recent Inn, also the Coach & Horses, which had been built nearby, was demolished to make way for a new road alignment in about 1975. Although writing in 1838, Dickens’ description appears to fit an earlier course of the road which clung to the side of the valley where the Butser Hill limeworks has subsequently eaten into the hillside.

The Turnpike Trust appears to have made some significant improvements to the road over Butser Hill. In 1826 an article appeared in the Portsmouth paper of the day giving a useful review of improvements to some of the local roads: “The roads in the vicinity of Petersfield have lately been most considerably improved and new communications are intended to be opened from which this place must speedily feel great benefit… The Portsmouth to London road has long been miserably bad at Butser Hill where the direction has been unnecessarily circuitous and being on the side of a hill the whole of the moisture soaks across the road. Ground has recently been purchased by the trustees to make this road straight by which the distance will be shortened by three furlongs. The new road will be 60ft lower than the present one”. Charles Harper, 19th century author of ‘The Portsmouth Road’, described the cutting as the largest and most spectacular road cutting in England.

Stage-Coaches, Smugglers and Highwaymen

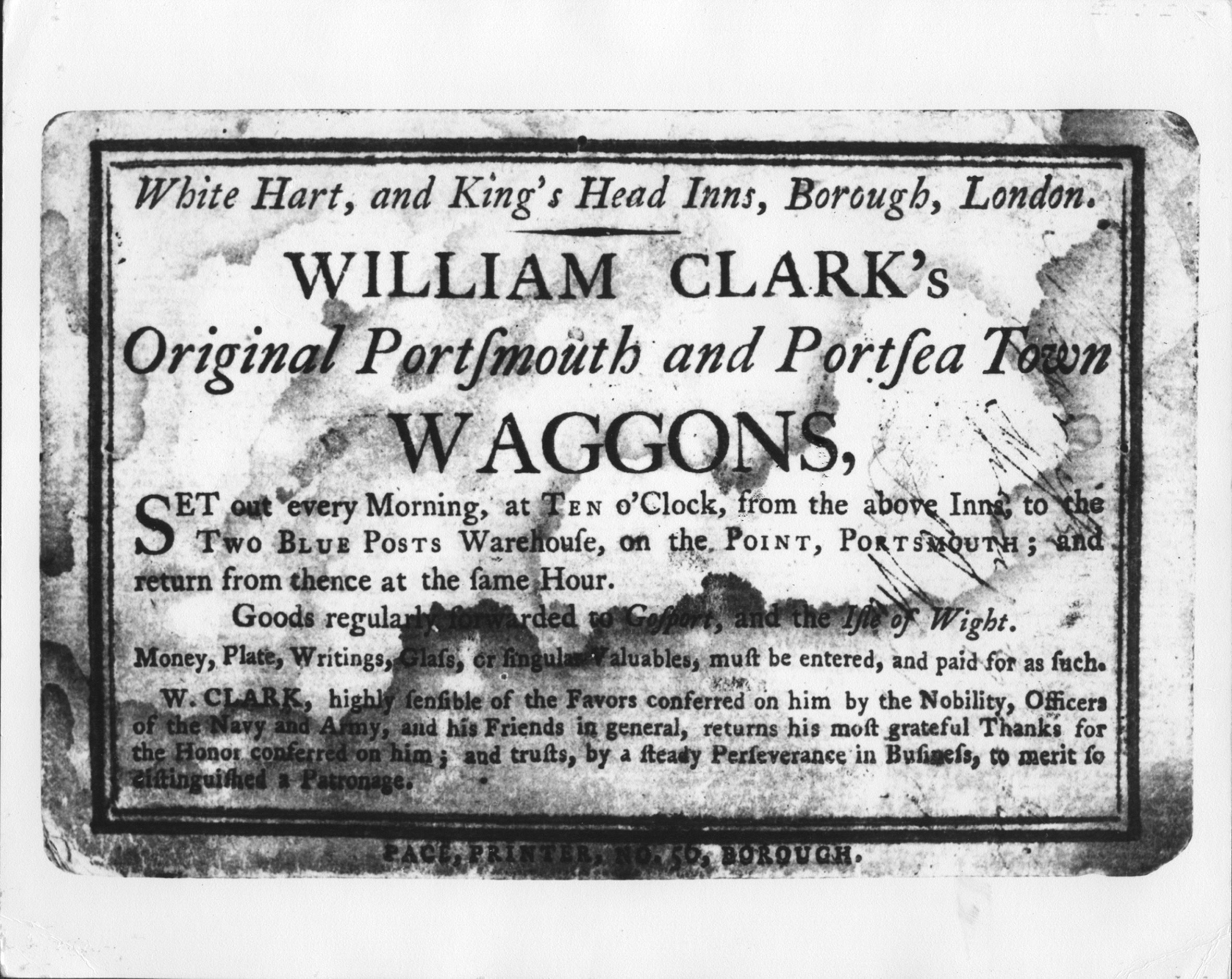

With improvements in the roads, regular horse-drawn stage-coach services between London and Portsmouth began in the eighteenth century although stage wagons (heavier clumsier vehicles) had probably operated for some time, taking about three days for the journey and being much used by sailors. In 1770 the quickest stage coaches took about 16 hours to complete the journey but by 1805 the number and speed of coaches was considerably improved. Passengers travelled on such coaches as the Nelson, the Hero, the Independent, the Regulator and the Rocket which would take about nine hours to do the journey. By the 1820s there were probably between eighty and a hundred scheduled coach services running along the road every week – perhaps a coach every half an hour during the day time.

But as the roads got busier, so too did the highwaymen. Slow speeds and the isolation of large areas of countryside meant that the Portsmouth Road, and particularly the section south of Petersfield, became notorious for an infestation of thieves. As Charles Harper, who wrote his book about the Portsmouth Road in 1895, explained, “… our forebears who prayerfully entrusted their bodies to the dangers of the roads and resigned their souls to Providence, were hurried along this route at the breakneck speed of something under eight miles an hour, with their hearts in their mouths and their money in their boots for fear of the highwaymen who infested the roads…” Coach guards carried large blunderbusses and cutlasses and people often made their wills before embarking on the journey. There were so many brutal murders on the route that the Portsmouth Road became known as the Road of Assassination.

A particular scourge of this area was James Allen, from Graffham, who made the section of road between Petersfield and Horndean his beat. He undertook some of the most impudent robberies in the area, always robbing on foot but making no scruple of firing at anyone who did not immediately submit to being robbed. It was never exactly known how many crimes he had committed, but his career came to an end in 1807 when, after a series of local robberies, a manhunt was organised and he was shot dead near Midhurst.

Not only was the Petersfield to Horndean area notorious for highwaymen but it seems to have been quite a smuggling centre in the middle of the eighteenth century – part of a network across the coastal counties of southern England. One of the greatest trades was in importing brandy and exporting wool. The area around the Hog’s Lodge Inn, where a nearby lane is still called Thieves Lane, appears to have been important. The lane leads to a small copse called Ditch Acre Copse whose ditches were reputed to have been the hiding places for contraband.

As well as the dangers of robbers and highwaymen, it seems likely that many coaching accidents would have taken place – particularly on the steep inclines of Butser Hill. Coaches could easily pitch onto one side while rattling down steep hills or around ugly corners and they could overturn completely into ditches. Although forbidden, racing between different coaches took place and undoubtedly made accidents more likely. Drunken sailors probably also caused occasional accidents and it would be a common sight to see a coach carrying 15 or 16 seamen, paid off from a ship that had been at sea for 3 or 4 years, on their way to London to spend their money. Coming the other way, a midnight coach from London sometimes brought gangs of convicts, chained together, bound for Portsmouth and transportation.

The end of the stage-coach era

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, fares for the journey between London and Portsmouth were £1 1s 0d inside and 12s 6d outside. Coaches generally carried no more than four passengers inside and eleven outside. It was probably very pleasant travelling on spring or summer mornings with bright sunshine on fresh green hedgerows. But in wintertime, the only person not frozen was probably the coachman, wrapped to the eyes in his many-caped greatcoat, whilst the miserable outside passengers, huddled together against the biting wind or driving sleet and strove to keep their toes from frostbite in a few wisps of straw.

The construction of railway routes between Portsmouth and London (from 1840) meant that travellers had an alternative to the coach road. Whereas the expansion of the stage-coach system had been spread over a period of seventy years or more, it contracted swiftly over about ten – with significant effects on some towns along the route. In the ‘golden age of coaching’ in the late 1830s there would have been about 1,200 people passing through Petersfield by stage-coach each week in the summer. By 1851 there were probably only 120 and only about six inward and outward coach movements a day. As Petersfield was an important staging post, there would have been a comparable reduction in the number of horses requiring stabling and in innkeepers’ business. Domestic servants, horse-keepers and stable-boys were laid off while local farmers undoubtedly suffered from the reduction in the demand for horse-feed.

After having its status renewed by Parliament a number of times, the Portsmouth and Sheet Turnpike Trust was wound up in 1871 after some 160 years – another victim of the railway boom. A number of significant improvements have, however, been made to the road since then. In 1898 Hampshire County Council spent £800 “grading back the chalky precipices” of Butser cutting because lumps of chalk used to regularly hurtle down onto the road below. A photograph from 1930 shows traffic on a “newly opened Butser cutting” and it is known that the road was dualled and/or straightened in 1975.

But sections of the old coach road probably still survive: high above the roar of the modern traffic on the A3 and above the old Butser Hill limeworks you may find a tiny white scar, just a few yards wide. Rutted and often deep in mud and chalk, it is difficult to think that it was once the mighty Portsmouth Road.